Diversification goes back in circles

RELATED PUBLICATION

ARTICLES FROM THIS PUBLICATION

Mining in Mongolia’s Economy

Image courtesy of SRK Consulting Mongolia

A small economy with a small population, tucked between Siberia and the Gobi Desert, with a harsh climate that swings from -40 to +40 Celsius, has few options for economic growth. Agriculture is mostly limited to livestock and at the mercy of the weather; manufacturing and trading are limited by the remote location and the lack of exit ports; and the service sector is constricted by the lack of a substantial domestic market. Mining remains Mongolia’s best shot, but relying too much on commodities holds perils too. On a good year, like 2023, mineral-export pushed GDP growth close to 6%. The opposite becomes true when commodity prices drop.

Mongolia is well aware of the risks of depending on mining alone. “It is anticipated that the economy will experience a surge in growth, surpassing 6% by 2024-2025, due to the rise in mining production. However, it is imperative to implement reforms that encourage economic diversification to maintain this growth and establish resilience against domestic, external, and climate-related disturbances,” said Altai Khangai, the CEO of the Mongolian Stock Exchange (MSE).

The main options for economic diversification are agriculture, value-added manufacturing, power, and tourism. Before the development of mining, Mongolia was mostly an agrarian economy, and the general economic advice was to diversify away from agriculture and into other sectors like mining. Now, the tables have turned, with the difference being that Mongolia is advised to develop a more technologically driven, sustainable, and integrated agri sector. For instance, instead of selling cashmere, it could process the raw material into yarn, deriving more value. The same principle would apply in the minerals sector. Companies like Oyu Tolgoi are talking about eventually producing cathodes, rather than simply copper concentrates in the future. Erdenes Mongol, the main state-owned enterprise that holds a stake in 30 different mineral companies (exploration, mining, logistics), also said it wants to build more processing plants.

Mongolia’s main opportunity outside of mining could be renewable power. The Asian Development Bank estimates that Mongolia could generate 5.45 terawatt-hours of clean wind and solar energy, which is about 62% of China’s electricity generation in 2022, reported the Lowy Institute. “Mongolia’s renewable resources are incredible. Mongolia is one of the sunniest locations; this, and the altitude, makes it ideal for photovoltaics,” said Oliver Schnorr, the CEO of Euro Khan, a company that eventually chose wind to generate green power in Mongolia at its Sainshand Wind Park.

The constraints of developing large-scale renewables are political, suggested the authors at the Lowy Institute article: If Mongolia were to export its green energy to China, the most obvious candidate for the purchase, it would tap into a gap that currently Russia fills, as an exporter of energy to both China and Mongolia. The disruption could upset the relationship between Mongolia’s only neighbors. China is building a US$12 billion solar project on its side of the Gobi. “China could build massive renewable plants in Mongolia, but Mongolia wants to guard its energy sovereignty as much as it can outside of China’s influence. Even Oyu Tolgoi is currently powered by a company in Inner Mongolia (Inner Mongolia Power Corporation),” said Schnorr.

The development of hydropower plants would also bump into a geopolitical obstacle, according to Schnorr: “Hydropower projects are a bit more problematic because the important Orkhon River is feeding into the Selenge, and the Selenge flows into Russia, draining into Lake Baikal. Russia would be alert if Baikal Lake levels dropped as a consequence.”

The careful courting of a third neighbor

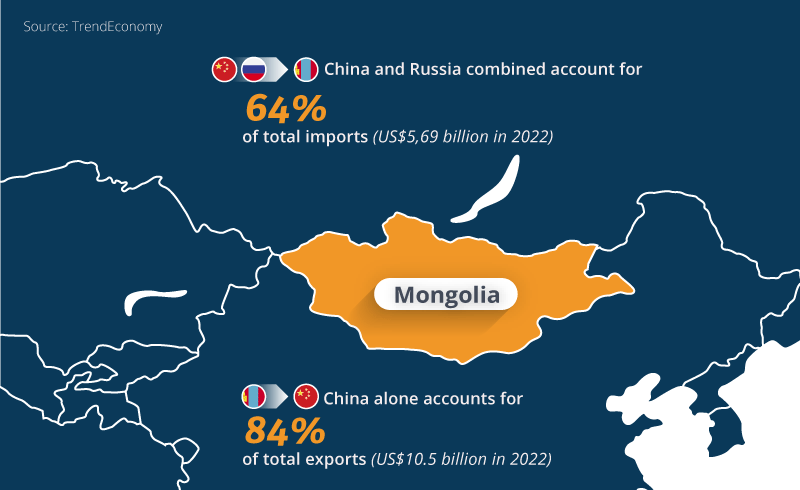

The invisible fences around Mongolia’s development are rooted in borders with only two neighbors, Russia and China. Mongolia is not only inescapably enclosed as a geography between the two, but it is also highly dependent on them. From Russia, Mongolia imports most of its critical fuel and energy; with China, on the other hand, Mongolia is bound through its exports, of which 90% are minerals and almost all go south to China. Landlocked, Mongolia also relies on its two neighbors logistically. Everything that reaches the Mongolian territory must go through Russia or China. Ever since international sanctions have been imposed on Russia, almost all cargo has been redirected through China. The sanctions have also deviated financial transactions, with most of Mongolia’s foreign trade being facilitated by Russian banks. The consequences of this tight encirclement by the two countries are easy to gauge: Should Russia decide it will no longer export oil to Mongolia, or China that it will no longer buy Mongolia’s copper and coal, Mongolia’s economy would be decimated. Despite its vast territory, Mongolia feels squeezed between its two neighbors, and has been wriggling in a delicate balancing act between maintaining good neighborly relationships and forging new relationships with what it calls ‘third neighbors’.

History taught the country about the risks of being bordered by two powerful nations. Mongolia was subjected to Chinese control as a province of China from the 17th to the 20th century, then, after a very short period of independence (1912-1919), Mongolia became a satellite state of the USSR, becoming the first Asian and second country in the world to adopt communism. Since its peaceful transition to democracy in 1990, Mongolia knew its freedom was fragile, so it must play both sides to protect itself. Recently, it was among one of only 34 countries that abstained from a non-binding UN peace resolution to demand Russia leave Ukraine and end the war. With Russia at war and less internationally available for cooperation, Mongolia has leaned more towards China, bolstering relationships on trade and infrastructure. The two neighbors have been working on the Power of Siberia 2, a proposed gas pipeline going from Russia to China via Mongolia. Mongolia’s coking coal exports to China are growing. “Lately, China has been reducing imports from Australia, the US, Canada, or Africa, prioritizing closer nations – Mongolia and Russia,” said Zolo Jargalsaikhan, executive director of the Mongolian Coal Association.

In parallel, Mongolia has also established “third neighbor” relations to counterbalance its overdependence on Russia and China. Eight third-country partners are prioritised: Japan, India, the US, Turkey, Germany, South Korea, Canada and Australia. The countries that exert the most cultural influence in Mongolia today appear to be Australia, especially through the connection of mining, Rio Tinto being an Aussie. The nickname of ‘Mozzie’, a Mongolian Aussie, has emerged to describe the growing number of Mongolians with Australian links. The most recent third neighbor on this list is the US, with which Mongolia signed the ‘Economic Cooperation Roadmap’ in August 2023. The US is particularly interested in the critical minerals supply chain. Likewise, a year earlier, Germany also looked to Mongolia as a potential future alternative supplier of critical minerals like copper and rare earths. France and South Korea show similar interests.

For the time being, mining remains the main source of FDI for Mongolia, just as China remains the biggest investor and main trading partner. Edward Faber, senior country economist at the Asian Development Bank, calls out a common bias: “When we think about investment, we too often see it from a Western perspective, of Western-led FDI, but Mongolia has tremendous advantages of being situated next to two very large trading partners and investors. It is crucial for the country to maintain solid relationships with its two neighbors. In terms of investment coming from further afield, distance plays a big factor, maybe more so than geopolitics.”