The under-explored gold-bearing grounds of West Africa are the “last frontier” in the gold space.

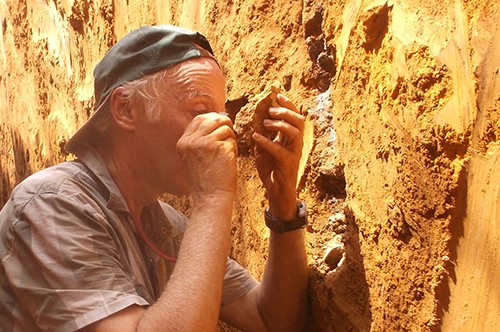

Image courtesy of Asante Gold

West Africa is home to extensive gold belts that host major mines including Barrick’s Luolo-Guonkoto complex, Gold Field’s flagship Tarkwa, AngloGold Ashanti’s Obuasi and IAMGOLD’s Essakane. With most producers operating at an AISC below US$1,000/oz, the gold spot price gravitating around the US$2,000 mark leaves these operators with handsome margins, boosting their cash flows and helping to reduce debt. But the junior space is also ready to benefit.

Following five years of hard times for raising exploration money, the junior sector is now enjoying a stronger investment appetite and a surge in M&A activity driven by the need to bring more assets into production. Large and mid-tier producers prefer to focus on bigger assets, opening room for smaller developers to grab projects in the range of 50-75,000 oz. Over the summer, mid-tier producers extended their portfolios through acquisitions: Perseus completed the acquisition of Exore Resources, taking over a land package of 2,000 km,2 together with the low-cost Sissingue mine in Ivory Coast; Mako Gold divested its greenfield Niou discovery in Burkina Faso to Russian producer Nordgold, which also made an offer to acquire Cardinal Resources, the Ghanaian success story around the tier-one Namdini gold discovery; in the meantime Barrick Gold announced selling its 80% interest in the Morila gold mine to Mali Lithium, a developer.

A news-flow of recent discoveries is also reinvigorating confidence in the exploration sector. In Guinea, Predictive Discovery showcased its Bankan asset, expected to be in excess of two million oz, West African Resources defined a high-grade, one million oz resource at its M1 South Shoot in Burkina Faso, while Chesser Resources is returning spectacular drilling results at its Diamba Sud in Senegal. On the back of returning investor sentiment and discoveries, juniors have seen major re-ratings and their capital placements heavily oversubscribed.

With an injection of both capital and enthusiasm, West Africa is perfectly suited to deliver the asset pipeline for this newfound demand: Besides low discovery costs, the turnaround times from discovery to production are very short. In only five years, Roxgold went from the first drill hole to the first pour at its Yaramoko mine in Burkina Faso. Moreover, easy metallurgy, with mostly open-pit, shallow mineralization, broadly characteristic to the region, offers an attractive development proposition at low CAPEX.

More significantly, however, is the huge upside potential for exploration. The region’s most mature market, Ghana, has been the home of discoveries totalling over 100 million oz to date, even though the country contains only 19% of the Birimian greenstone belt. By comparison, Ivory Coast holds 35% of this prolific geological structure, yet has seen little exploration. While the geological endowment is found across the Birimian stretch, external factors have to fall into place to attract investors dollars to one jurisdiction over another. An attractive fiscal code, political stability, and access to infrastructure play strongly into the choice.

The hotspots

If the previous cycle favored Burkina Faso and Mali, this time around Ivory Coast is the rising star in the region. Security is a key differentiator. Although the coup to remove Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta in Mali has been the most prominent issue in recent months, the violence in the Sahel region has spread outside of Mali, and Burkina is now the epicentre of the violence.

Meanwhile, Ivory Coast has seen a rush for permits. An early entrant in the country, Tietto Minerals is now looking at a resource of at least 2.2 million oz at its Abujar project, to be further updated later in October. Cameroon was popularised by Oriole’s discoveries at Bibemi and Wapouze: “While other West African countries are becoming more difficult to work in, Cameroon is becoming more stable and friendly for investors,” said Tim Livesey, CEO of Oriole Resources.

Meanwhile, there has been limited exploration in Ghana, with a couple of noteworthy exceptions including Azumah Resources and Cardinal Resources, as well as Goldstone, which is trying to bring back into production two historical mines, Akrokeri and Homase. Alfred Baku, country director for Gold Fields Ghana, commented: “Ghana is comparatively less attractive to other countries when looking at the benchmark for fiscal terms in exploration. The country is endowed with rich deposits, but without exploration, gold resources will simply reach exhaustion.”

Ghana is also suffering from a perception issue, as indicated by Simon Meadows Smith, managing director of SEMS Exploration Service: “Ghana is seen as a well-trodden jurisdiction, surrounded by countries with easier and better opportunities. That perception is wrong.”

Indeed, in the last gold cycle, explorers took licenses in Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Mauritania, only to later leave them due to higher operating costs.

Image courtesy of Asante Gold

West Africa is home to extensive gold belts that host major mines including Barrick’s Luolo-Guonkoto complex, Gold Field’s flagship Tarkwa, AngloGold Ashanti’s Obuasi and IAMGOLD’s Essakane. With most producers operating at an AISC below US$1,000/oz, the gold spot price gravitating around the US$2,000 mark leaves these operators with handsome margins, boosting their cash flows and helping to reduce debt. But the junior space is also ready to benefit.

Following five years of hard times for raising exploration money, the junior sector is now enjoying a stronger investment appetite and a surge in M&A activity driven by the need to bring more assets into production. Large and mid-tier producers prefer to focus on bigger assets, opening room for smaller developers to grab projects in the range of 50-75,000 oz. Over the summer, mid-tier producers extended their portfolios through acquisitions: Perseus completed the acquisition of Exore Resources, taking over a land package of 2,000 km,2 together with the low-cost Sissingue mine in Ivory Coast; Mako Gold divested its greenfield Niou discovery in Burkina Faso to Russian producer Nordgold, which also made an offer to acquire Cardinal Resources, the Ghanaian success story around the tier-one Namdini gold discovery; in the meantime Barrick Gold announced selling its 80% interest in the Morila gold mine to Mali Lithium, a developer.

A news-flow of recent discoveries is also reinvigorating confidence in the exploration sector. In Guinea, Predictive Discovery showcased its Bankan asset, expected to be in excess of two million oz, West African Resources defined a high-grade, one million oz resource at its M1 South Shoot in Burkina Faso, while Chesser Resources is returning spectacular drilling results at its Diamba Sud in Senegal. On the back of returning investor sentiment and discoveries, juniors have seen major re-ratings and their capital placements heavily oversubscribed.

With an injection of both capital and enthusiasm, West Africa is perfectly suited to deliver the asset pipeline for this newfound demand: Besides low discovery costs, the turnaround times from discovery to production are very short. In only five years, Roxgold went from the first drill hole to the first pour at its Yaramoko mine in Burkina Faso. Moreover, easy metallurgy, with mostly open-pit, shallow mineralization, broadly characteristic to the region, offers an attractive development proposition at low CAPEX.

More significantly, however, is the huge upside potential for exploration. The region’s most mature market, Ghana, has been the home of discoveries totalling over 100 million oz to date, even though the country contains only 19% of the Birimian greenstone belt. By comparison, Ivory Coast holds 35% of this prolific geological structure, yet has seen little exploration. While the geological endowment is found across the Birimian stretch, external factors have to fall into place to attract investors dollars to one jurisdiction over another. An attractive fiscal code, political stability, and access to infrastructure play strongly into the choice.

The hotspots

If the previous cycle favored Burkina Faso and Mali, this time around Ivory Coast is the rising star in the region. Security is a key differentiator. Although the coup to remove Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta in Mali has been the most prominent issue in recent months, the violence in the Sahel region has spread outside of Mali, and Burkina is now the epicentre of the violence.

Meanwhile, Ivory Coast has seen a rush for permits. An early entrant in the country, Tietto Minerals is now looking at a resource of at least 2.2 million oz at its Abujar project, to be further updated later in October. Cameroon was popularised by Oriole’s discoveries at Bibemi and Wapouze: “While other West African countries are becoming more difficult to work in, Cameroon is becoming more stable and friendly for investors,” said Tim Livesey, CEO of Oriole Resources.

Meanwhile, there has been limited exploration in Ghana, with a couple of noteworthy exceptions including Azumah Resources and Cardinal Resources, as well as Goldstone, which is trying to bring back into production two historical mines, Akrokeri and Homase. Alfred Baku, country director for Gold Fields Ghana, commented: “Ghana is comparatively less attractive to other countries when looking at the benchmark for fiscal terms in exploration. The country is endowed with rich deposits, but without exploration, gold resources will simply reach exhaustion.”

Ghana is also suffering from a perception issue, as indicated by Simon Meadows Smith, managing director of SEMS Exploration Service: “Ghana is seen as a well-trodden jurisdiction, surrounded by countries with easier and better opportunities. That perception is wrong.”

Indeed, in the last gold cycle, explorers took licenses in Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Mauritania, only to later leave them due to higher operating costs.