Portrait of the Turkey Pharmaceuticals industry.

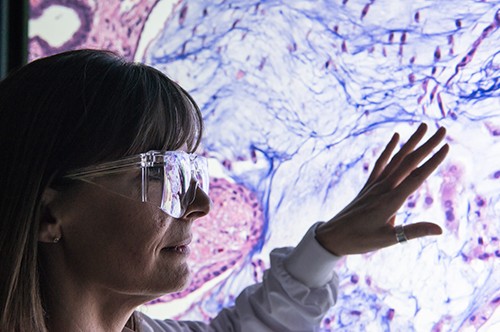

Image courtesy of AstraZeneca Turkey

In the offices of pharmaceutical companies across Istanbul, a portrait of the father of the Turkish Republic, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who engineered the transformation of Turkey into a modern nation state, hangs upon the wall. He is a suitable figure to watch over an industry that seeks to modernize and reinvent itself. With three years left until the centenary of the country’s creation, Turkey has ambitious plans to prove itself as a competitive economy on the international stage and the pharmaceuticals industry has been identified to play a lead role. As set out in the government’s Vision 2023, Turkey aims to become one of the top ten worldwide largest economies in health services.

The Turkish pharma industry is presently the 14th largest by value in the world, having moved up three positions over the last five years in IMS rankings. Out of the US$1.2 trillion estimated value of the global pharmaceuticals industry, the Turkish industry represents US$7 billion. The sector is characterized by a unique mix of high quality and low prices, a paradox achieved by a combination of tough international market standards and stringent domestic price controls.

Since the launch of the Healthcare Transformation Program in 2003, the government assures free healthcare coverage to 95% of the population. In taking the healthcare of the population under its responsibility, the government shifted part of this burden to industry, as the healthcare transformation program of 2003 included a reference price system to control the price of drugs and keep in check public spending on healthcare. The pressure stemming from this high-quality-low-price conundrum has led to the creation of a resilient industry, but one that has learned to prioritize survival before growth. Turkish pharmaceutical companies are currently running at half of their manufacturing capacity and, moreover, the drugs produced are primarily low-value generics while almost all originator drugs, as well as vaccines, blood products, biologicals and biosimilars are imported. Given this significant dependence on imports, internal market pressures are doubled by external price pressures. The macroeconomic volatility of the country has kept the pulse of the industry at a low pace and the economy crisis of 2018 stalled it further.

The future of Turkey’s pharmaceutical industry will largely depend on its ability to take advantage of a recent government impetus to develop the sector. The government’s incentives include increasing local production by rolling out a localization policy, ramping up exports to reduce the trade deficit, as well as developing the country’s biopharma sector. The focus on the pharma sector is partly due to its importance as the third largest contributor to Turkey’s trade deficit and to its potential to secure the domestic supply of medicines. With the interests of both the government and the industry approaching a convergence, the industry is bound to experience transformative shifts as it enters the 2020s.

Evolution of the market

The Turkish pharma industry is mature, but it is only in the last decade that the market has migrated from a low-margin, mass generics model to chronic therapies and biologics in a trend that aspires higher-value products. In the last 10 years, 200 new companies forced their entry into the generics market at a time when the government gave away generous incentives to kick-start a biotech sector. With increased competition in generics put in contrast to promising prospects in biopharma, the pharmaceuticals market is evolving to incorporate the prefix “bio” wherever possible. Atabay, a well-known leader in paracetamol, is an example: Just as the third generation took the helm of the company, investments in biopharma began.

While biopharma is gaining significant momentum, 80% of prescriptions remain in the domain of classical drugs. In this segment, the maturation of the product portfolios bears the signs of an industry overstretched by low prices and competition. Even if one in seven Turkish pharma companies is a local player, it is the foreign players that take 69% of market share by value. With multinationals like Sanofi claiming the leadership in popular chronic segments like CNS or cardiovascular disease, local players choose the niche therapies in which they stand a better chance of grabbing the first generic – the front line in the battle for the generics market. The localization policy introduced by the government in 2016 aims to give local players the upper hand by obliging all multinationals with products destined for Turkey to produce these products locally. This has led to more interaction between local and foreign players and a rise in collaborations for contract manufacturing. New companies and CMOs are already bracing for increased demand in different product categories. Regardless of the localization policy, a broader tendency has been to invest in difficult-to-make generics, like injectables or new radiopharmaceuticals.

Turkish pharma has evolved according to the challenges posed by the industry; however, the success of any strategy is conditioned by the pricing system, which is a constant point of return. In order to diversify the product basket or be competitive with a first or super generic, R&D efforts need to be commensurate. If increasing the product basket proves insufficient and companies instead look to increase the basket of countries they seek to operate in, profits in the domestic markets need to be lucrative to sustain expansion. The biopharma sector brings hope at the top of the pyramid for high-value products, but this is a capital-intensive sector sitting at odds with the cost-saving mentality that the industry has been forced to adopt. Besides finding the repertoire of drugs that can propel Turkey into world markets, as well as effectively responding to the needs of its 83 million population, Turkish companies are yet to make big strides to evolve from their current status. Perhaps it will take another decade or more before its model of growth will be proven right or wrong.

Image courtesy of AstraZeneca Turkey

In the offices of pharmaceutical companies across Istanbul, a portrait of the father of the Turkish Republic, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who engineered the transformation of Turkey into a modern nation state, hangs upon the wall. He is a suitable figure to watch over an industry that seeks to modernize and reinvent itself. With three years left until the centenary of the country’s creation, Turkey has ambitious plans to prove itself as a competitive economy on the international stage and the pharmaceuticals industry has been identified to play a lead role. As set out in the government’s Vision 2023, Turkey aims to become one of the top ten worldwide largest economies in health services.

The Turkish pharma industry is presently the 14th largest by value in the world, having moved up three positions over the last five years in IMS rankings. Out of the US$1.2 trillion estimated value of the global pharmaceuticals industry, the Turkish industry represents US$7 billion. The sector is characterized by a unique mix of high quality and low prices, a paradox achieved by a combination of tough international market standards and stringent domestic price controls.

Since the launch of the Healthcare Transformation Program in 2003, the government assures free healthcare coverage to 95% of the population. In taking the healthcare of the population under its responsibility, the government shifted part of this burden to industry, as the healthcare transformation program of 2003 included a reference price system to control the price of drugs and keep in check public spending on healthcare. The pressure stemming from this high-quality-low-price conundrum has led to the creation of a resilient industry, but one that has learned to prioritize survival before growth. Turkish pharmaceutical companies are currently running at half of their manufacturing capacity and, moreover, the drugs produced are primarily low-value generics while almost all originator drugs, as well as vaccines, blood products, biologicals and biosimilars are imported. Given this significant dependence on imports, internal market pressures are doubled by external price pressures. The macroeconomic volatility of the country has kept the pulse of the industry at a low pace and the economy crisis of 2018 stalled it further.

The future of Turkey’s pharmaceutical industry will largely depend on its ability to take advantage of a recent government impetus to develop the sector. The government’s incentives include increasing local production by rolling out a localization policy, ramping up exports to reduce the trade deficit, as well as developing the country’s biopharma sector. The focus on the pharma sector is partly due to its importance as the third largest contributor to Turkey’s trade deficit and to its potential to secure the domestic supply of medicines. With the interests of both the government and the industry approaching a convergence, the industry is bound to experience transformative shifts as it enters the 2020s.

Evolution of the market

The Turkish pharma industry is mature, but it is only in the last decade that the market has migrated from a low-margin, mass generics model to chronic therapies and biologics in a trend that aspires higher-value products. In the last 10 years, 200 new companies forced their entry into the generics market at a time when the government gave away generous incentives to kick-start a biotech sector. With increased competition in generics put in contrast to promising prospects in biopharma, the pharmaceuticals market is evolving to incorporate the prefix “bio” wherever possible. Atabay, a well-known leader in paracetamol, is an example: Just as the third generation took the helm of the company, investments in biopharma began.

While biopharma is gaining significant momentum, 80% of prescriptions remain in the domain of classical drugs. In this segment, the maturation of the product portfolios bears the signs of an industry overstretched by low prices and competition. Even if one in seven Turkish pharma companies is a local player, it is the foreign players that take 69% of market share by value. With multinationals like Sanofi claiming the leadership in popular chronic segments like CNS or cardiovascular disease, local players choose the niche therapies in which they stand a better chance of grabbing the first generic – the front line in the battle for the generics market. The localization policy introduced by the government in 2016 aims to give local players the upper hand by obliging all multinationals with products destined for Turkey to produce these products locally. This has led to more interaction between local and foreign players and a rise in collaborations for contract manufacturing. New companies and CMOs are already bracing for increased demand in different product categories. Regardless of the localization policy, a broader tendency has been to invest in difficult-to-make generics, like injectables or new radiopharmaceuticals.

Turkish pharma has evolved according to the challenges posed by the industry; however, the success of any strategy is conditioned by the pricing system, which is a constant point of return. In order to diversify the product basket or be competitive with a first or super generic, R&D efforts need to be commensurate. If increasing the product basket proves insufficient and companies instead look to increase the basket of countries they seek to operate in, profits in the domestic markets need to be lucrative to sustain expansion. The biopharma sector brings hope at the top of the pyramid for high-value products, but this is a capital-intensive sector sitting at odds with the cost-saving mentality that the industry has been forced to adopt. Besides finding the repertoire of drugs that can propel Turkey into world markets, as well as effectively responding to the needs of its 83 million population, Turkish companies are yet to make big strides to evolve from their current status. Perhaps it will take another decade or more before its model of growth will be proven right or wrong.