Tracking the complicated evolution of Sino-Congolese mining relations.

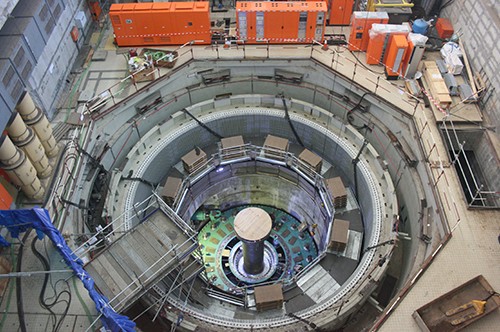

Image courtesy of Forrest Group

Although Sino-Congolese relations dates back to the mid-1960s when the Chinese Communist Party encouraged and offered support in the Congolese struggle against capitalism and American imperialism, China’s more palpable influence was marked by the 2008 infrastructure-for-minerals deal that attributed mining rights to China in exchange for substantial investment into the DRC’s war-torn infrastructure. In late 2007, a joint venture was set up to execute the terms of the agreement. It was named Sino Congolaise des Mines (Sicomines) and established with a Chinese majority shareholding of 68%. The Chinese US$6-billion investment was to be evenly divided between mining projects and the development of roads, railways, schools, hospitals and dams. While the publication of the deal, which was initially cloaked in secrecy and brought outcries from Western media and NGOs that raised the red flag of neo-imperialism and exploitation, it is easy to understand the Congolese government’s perception of China as an appealing trade partner. China has a perhaps unparalleled track record of rapid modernization, a process perfectly aligned with then- President Joseph Kabila’s model of “La Modernité.” Adding to the appeal was the absence of the ideological motivation that scarred the country during the United States’ involvement, as well as the permanent memory of the purely exploitive quest of King Leopold, eloquently described by author Joseph Conrad as the “vilest scramble for loot that ever disfigured the history of human conscience […]”. Thus, the framing was, as expressed by the Chinese government, a mutually beneficial relationship, absent of political conditionality where China would get access to the much needed minerals to supply its energy products, and the DRC would benefit from the building and repairing of its shattered infrastructure as well as the elevation of its productive capacity.

While the DRC’s estimated US$24-billion worth of minerals should in theory enable the country to replicate China’s economic miracle, the deal, confidently labeled at the time of its signing as “the deal of the century,” has not yet lived up to expectations. Under the agreement, China will receive 10 million tonnes (mt) of copper and 600,000 mt of cobalt at an estimated value of US$50 billion over a 25-year period. In 2016, domestic sources estimated that US$1.2 billion had been spent on infrastructure and mining credits combined.

In addition to the conspicuous disparity between the financial gains of the two parties, the projected positive impact of the deal rested on the false assumption that the DRC would have the ability to consolidate the Chinese investment efficiently. However, as the deal was purely framed in financial terms and omitted any guarantee of the actual benefit of the Congolese population, delays and unexpected costs due to tattered infrastructure and political volatility undermined the fairness of an already skewed agreement. This was further fueled by the neglect of good practice criteria when quality control was assigned to the same Chinese companies responsible for execution; the China Railway Engineering Company (CREC) and Sinohydro, which led to inadequate studies of environmental and social impact.

Chinese contribution to infrastructure was also agreed to be considered a debt until equal financial mining gains were made; thus the deal won tax exemption until infrastructure and mining loans were fully repaid. With a fair wind from politics and commodity prices, it is forecasted that revenues from the mining projects will cover the full infrastructure loans by 2026, or by a more pessimistic estimate, eight years later.

Yet, while certain aspects of the Sicomines deal could have been modified to better benefit the DRC, much of the blame for the so far suboptimal outcome lands at the feet of the country’s poor institutions and lack of infrastructure – a reality that would have negatively impacted any deal that could have replaced the one with China. In addition, as expressed by Mark Bristow, “There is a natural partnership to be had between the emerging Asian world and the Western capital base and the DRC is a perfect destination for that. The DRC is the axis of the future Africa in many ways – it is central, it is endowed with a large array natural resources and has the potential to be the energy flywheel of the African continent, with hard working and entrepreneurial people.”

Undoubtedly, the Sicomines deal has stimulated the entry of Chinese investors into the Congolese mining sector, injecting capital into the economy and providing much-needed work for the region’s millions of mostly impoverished residents. In 2013, six years after the signing of the deal, as many as 15 out of 143 firms reporting to the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) were Chinese; copper production increased from 200,000 mt/y in 2007 to 1.2 million mt/y in 2018, while cobalt production increased from 30,000 to 90,000 mt/y over the same period. Due to this development, the DRC’s macroeconomic performance has improved drastically, with total world trade balance in goods evolving from a deficit of US$783 million in 2007 to a surplus of US$208 million in 2017.

Thus, alluding to King Leopold-style imperialism as practiced ad naseum in Western media is a simplified narrative offering little guidance in determining China’s potential role as a valuable strategic partner in building a better future for the DRC. The most valid part of skeptical analysis is perhaps DRC’s growing dependence on China. Already in 2010, 80% of mineral processing plants in Katanga Province were owned by Chinese companies, and 90% of minerals extracted from Katanga mines were exported to China – the country’s main trade partner that received a total of 26% of exports in 2018. Considering the dysfunctionality of the Congolese state, an asymmetrical power relationship will, however, be the basis of any larger trade arrangement with the eventual potential to lift the DRC out of its historic role as a source of cheap resources serving the narrow interest of foreign capital.

Another critique, the basis of which is harder to validate, is concerning Chinese ethical conduct in the DRC’s extractive sector. Some evidence suggests that Chinese influence in the DRC has reversed a positive trend. While Congolese mining practices have been in a positive trajectory since the end of the civil war, the Lubumbashi-based NGO Premicongo released a report in November 2018 documenting environmental and socially unscrupulous conduct by China Nonferrous Metal Mining Corporation Huachin, which operates in Mabende in the Haut- Katanga region. The report lists issues such as deforestation, land pollution by wastewater, contamination of drinking water and restricted movement of the local population. Similarly, a 2017 Amnesty report documented children and adults mining cobalt in narrow man-made tunnels at DRC mine sites linked to the Chinese processing company Huayou Cobalt. The report assesses the progress that Huayou Cobalt and 28 companies potentially linked to it have made since the risk of child labor was revealed to them in January 2016, concluding that none of the companies named in the report are taking adequate action to comply with international standards.

On the flipside, there are indicators of China making advances in responsible sourcing and production across several areas. The China Chamber of Commerce of Metals Minerals and Chemicals Importers and Exporters (CCCMC) launched the Chinese Due Diligence Guidelines for Responsible Mineral Supply Chains in 2015 and was instrumental in launching the Responsible Cobalt Initiative (RCI) in 2016. According to RCS Global, an increasing number of Chinese producers and processors are also striving to bring company practices in line with international standards.

In the absence of adequate data offering a holistic understanding of Chinese conduct in the DRC, the only resort at hand is the vague speculation that the China story is nuanced. Moreover, if granted the same international scrutiny attributed to Chinese operators in the wake of the mammoth trade deal, the conduct of non-Chinese companies would likely be subject to the same muddy assessment of being a “mixed bag.” As stated by Bristow: “There are big, responsible Chinese resource companies that we work with shoulder to shoulder in the DRC. These are real, long-term, committed investors that are clear about returns and valuation, and want to participate alongside the government in the value they create just as we do.” He continued, “At the same time, there are some that are more entrepreneurial in their approach to business at the expense of a significant spectrum of stakeholders. This approach, however, is of course not limited to Chinese companies.”

The controversy continues down the supply chain, with equipment providers losing a share of the market to Chinese brands. According to Amaury Lescaux, managing director at Lubumbashi-based equipment provider Service Machinery and Trucks (SMT), “The industry has traditionally demanded two things; firstly, construction equipment and trucks with common components; and secondly, reliable production machines adapted to the heavy-duty usage of the sector,” He continued, “In the heavy duty range of mining equipment, the situation still remains the same but we do see a shift where mining companies and contractors would choose Chinese-made equipment for utility work and similar.”

Meanwhile, Patrick Thema, CEO of Groupe Thema that supplies trucks for Chinese company Sinotruk, sees Chinese machines as a way of benefiting the DRC by providing cheaper options at an increasing quality. “Our objective in the extractive industry is to spread the use of Chinese trucks that traditionally have been a secondary choice after European and American brands,” Thema said. “Today, Chinese trucks are becoming increasingly popular as the quality has been improved. So far, China has sold more than 1,500 trucks in the DRC across different sectors.”

Other equipment providers further voiced concerns over the potentially detrimental effect on local hiring. To what extent a transfer of skills to Congolese workers has been adequately bolstered by the Sicomines deal is hard to asses as few reliable employment statistics are available. According to news reports, some 75% of the 3,000 workers employed in the mining JV were Congolese as of 2015. On the infrastructure projects, around 4,000– 5,000 Congolese were working for CREC and Sinohydro in 2011, which at the time added up to about 17 Congolese per 235–275 expat Chinese workers.

The successfulness of the Sino-DRC relations must be judged on the merits of holistic improvements for the DRC as a country. By such measures, 10 years after its inception, the “deal of the century” has improved the DRC’s macroeconomic performance while also bolstering infrastructure developments, most notably the construction of roads in Kinshasa, the erection of a 450-bed hospital and a 240-megawatt hydroelectric power station planned to come online in 2021. Yet, the deal still has much to live up to and the future gains of the DRC will depend on both the country’s ability to consolidate the available benefits as well as the government’s resoluteness in ensuring that promises are kept.

Image courtesy of Forrest Group

Although Sino-Congolese relations dates back to the mid-1960s when the Chinese Communist Party encouraged and offered support in the Congolese struggle against capitalism and American imperialism, China’s more palpable influence was marked by the 2008 infrastructure-for-minerals deal that attributed mining rights to China in exchange for substantial investment into the DRC’s war-torn infrastructure. In late 2007, a joint venture was set up to execute the terms of the agreement. It was named Sino Congolaise des Mines (Sicomines) and established with a Chinese majority shareholding of 68%. The Chinese US$6-billion investment was to be evenly divided between mining projects and the development of roads, railways, schools, hospitals and dams. While the publication of the deal, which was initially cloaked in secrecy and brought outcries from Western media and NGOs that raised the red flag of neo-imperialism and exploitation, it is easy to understand the Congolese government’s perception of China as an appealing trade partner. China has a perhaps unparalleled track record of rapid modernization, a process perfectly aligned with then- President Joseph Kabila’s model of “La Modernité.” Adding to the appeal was the absence of the ideological motivation that scarred the country during the United States’ involvement, as well as the permanent memory of the purely exploitive quest of King Leopold, eloquently described by author Joseph Conrad as the “vilest scramble for loot that ever disfigured the history of human conscience […]”. Thus, the framing was, as expressed by the Chinese government, a mutually beneficial relationship, absent of political conditionality where China would get access to the much needed minerals to supply its energy products, and the DRC would benefit from the building and repairing of its shattered infrastructure as well as the elevation of its productive capacity.

While the DRC’s estimated US$24-billion worth of minerals should in theory enable the country to replicate China’s economic miracle, the deal, confidently labeled at the time of its signing as “the deal of the century,” has not yet lived up to expectations. Under the agreement, China will receive 10 million tonnes (mt) of copper and 600,000 mt of cobalt at an estimated value of US$50 billion over a 25-year period. In 2016, domestic sources estimated that US$1.2 billion had been spent on infrastructure and mining credits combined.

In addition to the conspicuous disparity between the financial gains of the two parties, the projected positive impact of the deal rested on the false assumption that the DRC would have the ability to consolidate the Chinese investment efficiently. However, as the deal was purely framed in financial terms and omitted any guarantee of the actual benefit of the Congolese population, delays and unexpected costs due to tattered infrastructure and political volatility undermined the fairness of an already skewed agreement. This was further fueled by the neglect of good practice criteria when quality control was assigned to the same Chinese companies responsible for execution; the China Railway Engineering Company (CREC) and Sinohydro, which led to inadequate studies of environmental and social impact.

Chinese contribution to infrastructure was also agreed to be considered a debt until equal financial mining gains were made; thus the deal won tax exemption until infrastructure and mining loans were fully repaid. With a fair wind from politics and commodity prices, it is forecasted that revenues from the mining projects will cover the full infrastructure loans by 2026, or by a more pessimistic estimate, eight years later.

Yet, while certain aspects of the Sicomines deal could have been modified to better benefit the DRC, much of the blame for the so far suboptimal outcome lands at the feet of the country’s poor institutions and lack of infrastructure – a reality that would have negatively impacted any deal that could have replaced the one with China. In addition, as expressed by Mark Bristow, “There is a natural partnership to be had between the emerging Asian world and the Western capital base and the DRC is a perfect destination for that. The DRC is the axis of the future Africa in many ways – it is central, it is endowed with a large array natural resources and has the potential to be the energy flywheel of the African continent, with hard working and entrepreneurial people.”

Undoubtedly, the Sicomines deal has stimulated the entry of Chinese investors into the Congolese mining sector, injecting capital into the economy and providing much-needed work for the region’s millions of mostly impoverished residents. In 2013, six years after the signing of the deal, as many as 15 out of 143 firms reporting to the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) were Chinese; copper production increased from 200,000 mt/y in 2007 to 1.2 million mt/y in 2018, while cobalt production increased from 30,000 to 90,000 mt/y over the same period. Due to this development, the DRC’s macroeconomic performance has improved drastically, with total world trade balance in goods evolving from a deficit of US$783 million in 2007 to a surplus of US$208 million in 2017.

Thus, alluding to King Leopold-style imperialism as practiced ad naseum in Western media is a simplified narrative offering little guidance in determining China’s potential role as a valuable strategic partner in building a better future for the DRC. The most valid part of skeptical analysis is perhaps DRC’s growing dependence on China. Already in 2010, 80% of mineral processing plants in Katanga Province were owned by Chinese companies, and 90% of minerals extracted from Katanga mines were exported to China – the country’s main trade partner that received a total of 26% of exports in 2018. Considering the dysfunctionality of the Congolese state, an asymmetrical power relationship will, however, be the basis of any larger trade arrangement with the eventual potential to lift the DRC out of its historic role as a source of cheap resources serving the narrow interest of foreign capital.

Another critique, the basis of which is harder to validate, is concerning Chinese ethical conduct in the DRC’s extractive sector. Some evidence suggests that Chinese influence in the DRC has reversed a positive trend. While Congolese mining practices have been in a positive trajectory since the end of the civil war, the Lubumbashi-based NGO Premicongo released a report in November 2018 documenting environmental and socially unscrupulous conduct by China Nonferrous Metal Mining Corporation Huachin, which operates in Mabende in the Haut- Katanga region. The report lists issues such as deforestation, land pollution by wastewater, contamination of drinking water and restricted movement of the local population. Similarly, a 2017 Amnesty report documented children and adults mining cobalt in narrow man-made tunnels at DRC mine sites linked to the Chinese processing company Huayou Cobalt. The report assesses the progress that Huayou Cobalt and 28 companies potentially linked to it have made since the risk of child labor was revealed to them in January 2016, concluding that none of the companies named in the report are taking adequate action to comply with international standards.

On the flipside, there are indicators of China making advances in responsible sourcing and production across several areas. The China Chamber of Commerce of Metals Minerals and Chemicals Importers and Exporters (CCCMC) launched the Chinese Due Diligence Guidelines for Responsible Mineral Supply Chains in 2015 and was instrumental in launching the Responsible Cobalt Initiative (RCI) in 2016. According to RCS Global, an increasing number of Chinese producers and processors are also striving to bring company practices in line with international standards.

In the absence of adequate data offering a holistic understanding of Chinese conduct in the DRC, the only resort at hand is the vague speculation that the China story is nuanced. Moreover, if granted the same international scrutiny attributed to Chinese operators in the wake of the mammoth trade deal, the conduct of non-Chinese companies would likely be subject to the same muddy assessment of being a “mixed bag.” As stated by Bristow: “There are big, responsible Chinese resource companies that we work with shoulder to shoulder in the DRC. These are real, long-term, committed investors that are clear about returns and valuation, and want to participate alongside the government in the value they create just as we do.” He continued, “At the same time, there are some that are more entrepreneurial in their approach to business at the expense of a significant spectrum of stakeholders. This approach, however, is of course not limited to Chinese companies.”

The controversy continues down the supply chain, with equipment providers losing a share of the market to Chinese brands. According to Amaury Lescaux, managing director at Lubumbashi-based equipment provider Service Machinery and Trucks (SMT), “The industry has traditionally demanded two things; firstly, construction equipment and trucks with common components; and secondly, reliable production machines adapted to the heavy-duty usage of the sector,” He continued, “In the heavy duty range of mining equipment, the situation still remains the same but we do see a shift where mining companies and contractors would choose Chinese-made equipment for utility work and similar.”

Meanwhile, Patrick Thema, CEO of Groupe Thema that supplies trucks for Chinese company Sinotruk, sees Chinese machines as a way of benefiting the DRC by providing cheaper options at an increasing quality. “Our objective in the extractive industry is to spread the use of Chinese trucks that traditionally have been a secondary choice after European and American brands,” Thema said. “Today, Chinese trucks are becoming increasingly popular as the quality has been improved. So far, China has sold more than 1,500 trucks in the DRC across different sectors.”

Other equipment providers further voiced concerns over the potentially detrimental effect on local hiring. To what extent a transfer of skills to Congolese workers has been adequately bolstered by the Sicomines deal is hard to asses as few reliable employment statistics are available. According to news reports, some 75% of the 3,000 workers employed in the mining JV were Congolese as of 2015. On the infrastructure projects, around 4,000– 5,000 Congolese were working for CREC and Sinohydro in 2011, which at the time added up to about 17 Congolese per 235–275 expat Chinese workers.

The successfulness of the Sino-DRC relations must be judged on the merits of holistic improvements for the DRC as a country. By such measures, 10 years after its inception, the “deal of the century” has improved the DRC’s macroeconomic performance while also bolstering infrastructure developments, most notably the construction of roads in Kinshasa, the erection of a 450-bed hospital and a 240-megawatt hydroelectric power station planned to come online in 2021. Yet, the deal still has much to live up to and the future gains of the DRC will depend on both the country’s ability to consolidate the available benefits as well as the government’s resoluteness in ensuring that promises are kept.